“As long as you write, you’ll always have something to write about.” -Frank McCourt

Although I had been introduced by the organiser to Frank McCourt at the first Ottawa International Writer’s Fest, and had him sign a copy of Angela’s Ashes, with the words “To a fellow scribe,” I had never read the book. I hadn’t read much at that point. I was 24. I was worried it would affect my voice as a young poet. I was just about to publish my first book of poetry, “A Bleeding Hand in Central Park,” and imagined that the following book would come out by the time I was thirty. Six years seemed like enough time to get in trouble, reflect on my survival, and then edit the adventures into something marketable. The trouble I got into produced a lot of stories, but very little incentive to come back to my publisher with a follow-up.

Since that time, I have taught in South Korea, Canada, and for the last twenty years, Japan. I’m now typing this in the August of my 47th summer. By McCourt’s measure, I still have plenty of time to write a bestseller. As for storytelling, I have the opportunity to do so in my lectures, at ROR open-mics in Osaka, Pecha Kucha presentations in Hyogo, or during walking tours of the tachinomis (standing bars) of Sennichimae in Namba. All these opportunities give me a chance to craft my stories for each new group of people I meet.

In his third and final memoir, McCourt mentioned the myth of ATTO, or All That Time Off, the myth that is perpetuated with congratulatory envy over what everyone assumes a teacher’s summer to be. But I am here in my living room, trying to make sense of the data points that I need to grade students. It’s been a month since classes ended, and even still there are students sending me essays to grade. I have weeks until official grade submission but I found it difficult to get through the mundane task of reading essays online, and then in Excel, giving each one a mark. It is some respite that you need not comment on each paper, but still it takes days. Each class, each course, has it’s on formula, like black magic spells, to conjure up the worth of the student’s effort in letter-grade form. I want to be done with it all. Attempt to make McCourt’s myth a reality. But like him, I’m a guilt-ridden catholic, ensuring I don’t succumb to the heartless grading that the masters seem to get done before the last bell rings. How else could they already be on planes to Athens, the UK, or Thailand, already reuniting with friends, family, and favourite cocktails.

It’s been difficult to find time to get away from the city. My wife and daughter have both begun part-time work, limiting the chance for our traditional summer camp getaways. I have taken time to mourn the passing of a friend, helped to clean his apartment, raise funds for the funeral and delivery of his remains to family in the States. I learn that all life is priceless, but unless you have someone to haggle for you, the cost of bringing home the dead is anywhere from 450,000 yen to 700, 000 yen. It’s reassuring to know that the cost of a round-trip ticket is still cheaper than this one-way delivery.

We had plans to make a road trip to a friend-owned guesthouse in Kochi Prefecture. When my wife saw news that a typhoon was arriving the day we were to begin our three-day getaway, she suggested that we cancel our stay. It’s irresponsible to consider braving something as powerful as a tropical storm during a trip, but when you live in Japan, you get accustomed to these summers spells a Cincinnati friend once described as “Mother Nature just breathing heavy.” And in the lush mountain surroundings of Kochi, the rain and winds would surely add to the beauty, rather than detract. My daughter agreed. If we are going to be stuck inside, might as well do it from a remote guest house where we can (don’t laugh) get work done.

We were greeted by David and Yoshiko when we arrived at Sorayama Guest House on August 8. They had been living here for 4 years, spending most of the pandemic to renovate it with funding from the government that covered 75% of the expenses. They were just as happy as us to welcome the typhoon. Most of the guests had cancelled their reservations. It would just be the six of us, their daughter and ours. We would have the guest house and by extension the river along side of it to ourselves.

Niyodo River is known for it’s crystal clear blue river water sourced from the mountain tributaries that make up most of Kochi. At it’s widest point, the river has room for day trippers to park their cars on its dry shore, unless it is August when crowds come down for the Mizukiri (stone skimming) Championship held at Hakawa Park, on the riverbed in front of Niyodogawa Bridge.

On our first day, we could see three massive carp relaxing in shallow waters of a stony beach David had cleared of river weeds. We tried to find the rope-swing next door for fast access to the water, but were told it had been taken down just before the typhoon. We had just arrived and though it rained, there was still optimism that with our arrival, things would clear up.

They did not.

By the next morning, there was no sign of carp, or stony tranquil shores. There was just the raging chaotic rush of water the colour of chocolate milk passing below. The water was higher, and louder. At night, we could barely make out the sound of our phones’ emergency notifications because they had been drowned out by the rush of water that was so constant, it sounded like snowy tv channel static but deeper, hollower, and relentless.

At four am, I woke up to see what state the river was in, but nothing could be known until the sun made visible this mountain pass. Mayuko had decided it was best to evacuate. The mountain roads were narrow and the tires of cars passing by did so with sound of water being displacing over ever-longer distances. If any road suffered a landslide, we wouldn’t know when to make it back. Yoshiko and David thanked us for the visit, we thanked them for the incredible breakfast, and for the previous night’s fire made under a fire-resistant tarp that sheltered us from the rain, and protected the upstairs rooms from smoke damage.

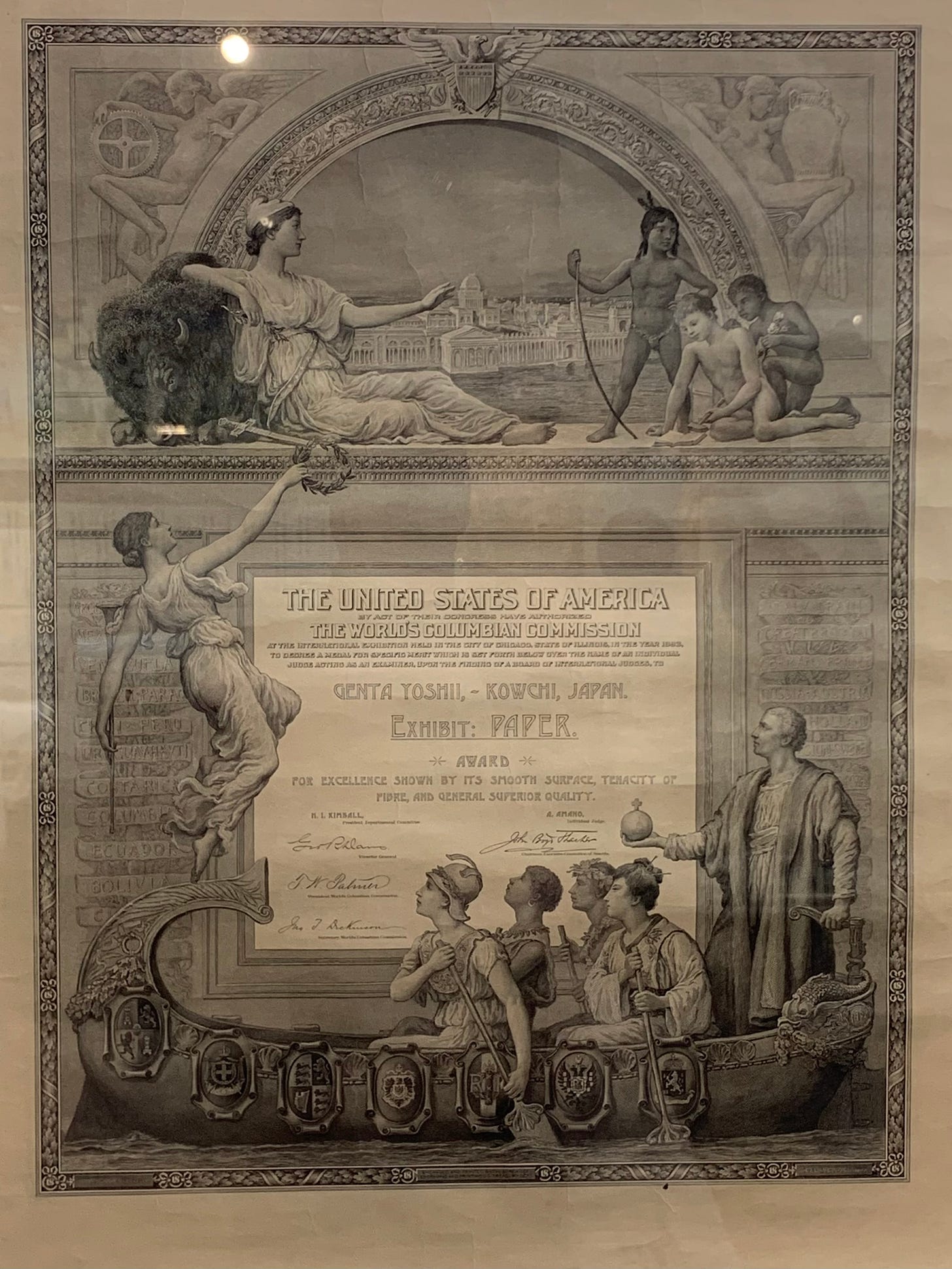

I didn’t get to do much exploring, but did learn a considerable amount about Kochi’s renowned washi, paper used for writing, craft, and fine art restoration. A visit to the local paper museum showed me why it, like most traditional Japanese materials made by hand, is superior to the mass produced, machine-made variety.

Since returning home safely, we have heard that Sorayama Guest House and all of Ino, Kochi, has been spared any damage from the heavy rain and floods. The carp have returned to the shallow banks, but David has more work to do hacking back the river weeds. We have promised to come back when it is time to cut down the kozo or mulberry branches used to make washi. They have assured me that when the time comes, I’ll be pulled into every step of the paper making process by locals who, though friendly, energetic and outgoing, would happily take a break from the painstaking work while the new kid works with gusto once he finds the rhythm of this arduous labor soothing.

What else is there to do with All That Time Off? By the end of next semester, I may have a system for grading papers more efficiently. If not, I’ll find my bliss making Grade-A paper, the Kochi way.